Will Utilities Survive the Transition to Clean Energy?

You still read the newspaper don't you? Less than before, perhaps intermittently so. But it is still a good backup for TV, Facebook, Google and the Internet. Will the same be true with electricity from traditional utilities? History suggests although utilities will add wind and solar to the generation mix, deploy a fleet of batteries and engage in EV charging, it is likely many will fail to successfully transition their business to take advantage of the electricity markets of the future. Why?

The monolithic utiltity model is transitioning to a disparate, competitive, consumer focused and highly interconnected energy and related services model

open to new entrants and competitors.

Most utilities will wait until their legacy business starts declining

before acting decisively to compete in the new world -- it will be too late.

Utilities will gradually incorporate the new technologies but will be slow

to incorporate or adapt to the new business models those technologies enable.

We have examined a series of other industries as they have undergone similar multi-decade long transitions in the face of disruptive technologies. The consistency of behavioral patterns amongst large incumbents and the greater agility of the newcomers again and again signals it is unlikely that most big incumbents will be successful in transitioning their business. The three charts below reflect patterns that reappears across almost all industries in transition due to disruptive technologies.

THE UTILITY IN TRANSITION: LESSONS FROM OTHER INDUSTRIES

Over the last thirty years, industry after industry has undergone fundamental transformation at the hands of new and disruptive technology. For CEO’s, boards and shareholders of incumbent businesses whose industries have not yet faced these technological disruptions, and particularly for those facing them today, there are important lessons to be learned from those prior transitions.

We have focused on four industries where the change was obvious, slow moving (i.e. took more than ten years) and where virtually none of the incumbent players successfully made the transition. The four industries we have used are (i) the publishing industry; (ii) the music industry; (iii) the photography industry, and (iv) the telecommunications industry.

In all four cases change didn’t come as a surprise, the growth of the new was quite gradual at first but continued relentlessly once it was underway. In all four cases, the old world industry continued its own growth during the early years of the onslaught of the new. In all four cases the incumbents of the old tried desperately to transition their own business to the new and failed. But most importantly, in each case technology served to create new market opportunities inaccessible via the old technology. Lastly, in two cases, even the disruptive technology was rapidly itself disrupted by a second wave of innovation; typically one more focused on new business models than on new technologies.

1. The Publishing Industry -- Newspapers.

The Internet didn’t sneak up on either the publishing or advertising industries. Most saw it coming in the 1990’s; it should have been obvious to all by 2000.

But, as the above chart [Note 1] shows, the brief recession in 2000 could allow Internet skeptics to argue that the new technology had just been a bubble and was being reduced to its “proper place” in 2001 and 2002. Only when it became clear by 2004 or 2005 that the Internet was far from dead, did many newspapers take matters seriously, but, by then, it was already far too late.

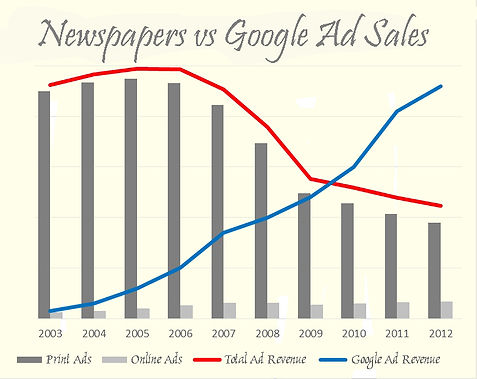

The growth in Internet advertising dollars has been particularly acute for the newspaper business. Most newspapers clearly saw it coming and tried to build their own Internet businesses. The problem was that no matter how successfully you built your online business, your legacy business was shrinking at a far, far faster rate.

As the chart [Note 2] above indicates, newspaper online advertising did grow as newspapers realized they had to move online (albeit slowly). The problem is that digital revenues (for newspapers) grew too slowly while their print ad revenues went into steep decline by 2006. Arguably newspaper executives had almost ten years to prepare themselves for the change.

The problem was that the digital ad business for newspapers just isn’t competitive with Google’s digital ad business (or that of Facebook or other new online media). Newspapers painfully discovered that their content is not distinguishing enough to satisfy digital subscribers; forcing them to cut newsroom and other staff and reduce frequency of circulation (e.g. going to three days a week); ultimately forcing more and more of them to conclude their business was just no longer viable. From a news journalist’s perspective, newspapers have always been an indirect cross-subsidy of soft-news advertising paying for hard-news journalism. Because online search gives advertisers a more direct way to reach those soft-news readers, that is where the ad revenue dollars moved.

The Washington Post was one company that actually did a nice job of building its online business — online accounts for 43 percent of its overall revenue, up from just 10 percent in 2004. But, The Washington Post lost five dollars in print revenue for every dollar it added in the form of online ad revenue — losing almost $90 million in print revenue while its online business grew by less than $20 million. In December 2004 the Post’s stock traded at $1,000 a share, by March 2009 it was down to $322 per share. The Post’s Newsweek division, which started bleeding cash in 2008 was sold for $1 plus assumption of debt in 2010. Why? Three main reasons: (i) the Internet just offers too much free and superficially similar content; (ii) new competitors (like the Huffington Post) have done a better job of being digital; and (iii) there has been continuous downward pressure on ad prices as the amount of content grew explosively.

None of this happened overnight. In fact even with the very obvious threat of the Internet, newspaper ad revenues continued to grow until 2005. That was the year the Huffington Post got started. It took five years for the Huffington Post to show an annual profit (December 2010), but in February 2011 it was sold to AOL for $300 million.

The continued growth of the old (even after the disruptive new technology is obvious) creates what Clay Christensen refers to as “The Innovator’s Dilemma.” In case after case, companies with a commanding lead in their field, whether it’s hard-drive makers, steel mills, or newspapers are almost incapable of taking the steps that need to be taken to survive a technological and/or behavioral disruption — even when the danger of not doing so is blindingly obvious. In other words, even when a company can see quite clearly that a freight train is approaching or a cliff lies directly ahead, it is still almost impossible to step off the tracks or do anything other than stampede over the edge. The fact that your legacy business continues to grow in the early years (right when you need to be making changes) makes it all the more difficult, particularly for CEO’s trying to manage quarterly earnings calls.

As Christensen described it and the chart [Note 3] below shows, “even as the disruption is getting more and more steam in the marketplace, the core business persists, and is really quite profitable for a very long time.

Then, when the disruption gets good enough to address the needs of your customers, very quickly, all of a sudden, you go off the cliff.”[Note 4] After five decades of very health revenue growth, understanding that you would lose it all in the next decade seemed farfetched to most newspaper owners.

So even though newspapers clearly should have seen the writing on the wall; virtually all of them have been incapable of making the decisions needed to get in front of that wave of disruption, particularly since doing so seemed likely to cannibalize their existing business model. Interestingly, Christensen’s advice to newspapers was: “aggressively cut your costs on the traditional side of the business and invest heavily in the new digital businesses;” acknowledging that most papers began to excel at the former even as they struggled with the latter, meaning they learn to decline gracefully not learn to adapt.

2. The Publishing Industry -- Books and Magazines.

The story was really no different in the magazine or book publishing industries. In fact, for brick and mortar book stores, it is unclear that there was anything they could have done to stave off Amazon. Perhaps more importantly, Amazon innovated twice, in some ways taking the difficult step of cannibalizing itself. The first innovation was on-demand publishing sold online and delivered after the customer had paid – reducing inventory and receivables costs. But the second innovation was the Kindle, removing the need for paper or physical delivery. The impact on the bookstore industry is obvious from the chart [Note 5] below:

Here too, it was obvious that Amazon was growing rapidly long before the period between 2006 and 2009 that was similarly the turning point for bookstore revenues.

3. The Music and Video Industries -- Physical to Digital.

Digital had a similar impact on the music and video industries, arguably industries that should now be quite familiar with wave after wave of technology disrupting a technology that still seemed in its nascent years. Here too two simple charts [Note 6] tell the story:

As with books, the replacement of the physical media with a digitally deliverable form of content, put record stores and CD stores effectively out of business. So even if you were successful at transitioning your record store to one selling CDs and DVDs, the combination of iPods, digital streaming and Netflix swiftly came along and put even those nimble stores out of business. As the chart [Note 7] on the left shows, the initial shifts were media changes from VHS to DVD to Blu-Ray, but ultimately, the devastating blow came from the switch from physical media to downloadable and then streaming media (see chart on right [Note 8]) with Blockbuster having seen the early transition, but missing the latter and Netflix effectively cannibalizing its own mail business by then offering streaming movies which completely eliminated any physical goods transfer.

This is a critically important phenomenon that CEO after CEO and Board after Board misses: Not only does the new technology require you to shift from old to new, but the new typically enables business models that simply weren’t possible at all with the old and thus were nonobvious or invisible to those faithfully doing their best to transition to the new technology while retaining their legacy business model. Further, the newer business models generally open doors to entirely new markets that are often far larger than the markets characterized purely by shifts in hardware technologies.

4. The Photography Industry-- Film to Digital to Phone.

The next industry to illustrate these changes is the photography business. Compare the chart on the left below to the newspaper ad revenue chart above under the Newspapers heading. Here, one might argue that change came fairly suddenly as the growth of digital cameras started to take off in 1995 (see chart below), and the cliff for film cameras came as soon as 1999. But film itself seemed to hang on longer, causing senior executives at Kodak to make the critical decision to preserve the film business rather than move to digital (a technology Kodak had actually itself been an early inventor of [Note 9]), a decision that ultimately killed the company.

However, here too the story doesn’t end at digital cameras replacing film cameras. So even if Kodak had made that leap, they may well have missed the second leap – the rapid rise of the camera in the cell phone. In fact, the modern cell phone single-handedly did in both the initial digital music (CD) industry and the digital camera industry. See chart [Note10] below:

5. Communications -- Same Story but in a Regulated Industry.

All of the prior examples have been of consumer products, so what relevance do their stories have for modern electric utilities?

That’s probably what executives at AT&T thought as well. First, recognize that solar panels, batteriesd and electric vehicles are also consumer products. Secondly, the regulated phone and telecommunications industry shows that a quasi-monopolistic utility business is not immune from the forces of change and, worse; that it too can suffer from the same transformation of business model that moves the fundamental business beyond the competence of the former industry leaders. Note in the chart [Note11] below, not just the switch from landline to mobile, but the far more rapid rise of the new businesses that captured an ever increasing share of the globe’s person-to-person communications:

Here too, the pattern repeats itself. Although mobile phones started to accelerate their growth in the early 1990’s, landlines continued their growth as well, not starting their decline until 1999 – at a point where the number of mobile subscribers had almost caught the number of landline users. For legacy Telco’s the problem was that even as their usage minutes grew, their revenue per minute crashed [Note12].

But, as with newspapers, cameras and music, the real big business opportunity was not the shift from the old technology to the new, it was the completely new user experience that the new technology enabled – in this case the much richer communication channels (like Facebook) that the Internet enabled. How likely was it that landline communications companies were going to be able competitors in not just Facebook or Linked-in posts, but in tweets, snap-chats, texting and the myriad of other ways that we now exchange digital information?

6. Lessons for Electric Utilities.

What are the key takeaways from these other industries undergoing transformation for the electric power industry?

First, if you wait until your own business starts to decline, it is already far too late.

The reality is that you should be using those last few years of robust old world growth to aggressively fund your move into the new world. When you wait until your legacy business is in decline, the first thing you will need to do is rapidly cut costs. All of a sudden, the excess cash that could have funded the transition is no longer there. You are defending your life to your stockholders and they are unlikely to be charitable about your suddenly spending cash to be a late entrant into a new business you aren’t good at. Justifiably so.

Second, just incorporating the new technology into your old way of doing business

is not a winning strategy.

In almost all cases, the new technology opens doors to new business models and new revenue streams that previously just didn’t exist. Often they are businesses quite different from the one that you are good at (like trying to turn a great brick and mortar book store into a great deliverer of online content). So it isn’t just the new technology that is disruptive, it is the new products, services, business models and customers that new technology enables and the secondary effects that come from opening those new doors. The reality is that neither you nor your senior executive team is going to be good at transitioning your business into those disparate new worlds.

Third, what was once a single mature business may now be

two, three or more nascent, rapidly moving and evolving businesses.

If you want to keep up you have to play in all of them. Even companies that themselves were major disruptors – Intel, Cisco, Microsoft, Apple, Google and others – have struggled to keep up in this kind of rapidly changing world. As a defensive measure, each of them has intentionally built a culture focused on rapid and continuous change and disruption.

Let’s say you are a utility executive facing the change in the power industry. Wind and solar have already staked out meaningful positions and anyone who thinks they are going away or slowing their growth would do well to look again at the first chart on Internet Ad Revenue growth. The 2008-2011 recession and its impact on renewable energy might look just like the Internet recession of 2000 by the time you wake up.

Because of the German government’s political decision to increase wind and solar penetration, the German utilities serve as a useful early warning system for what the broader utility industry is likely to face. The following charts repeat many of the patterns shown above. The first is the growth in renewable energy (Chart below on left [Note13]), the second is the impact that growth is having on wholesale electric prices (Chart below middle[14]) and the third (Chart below on right) is the resultant impact on utilities stock prices. How many of these utilities saved enough cash in the run-up of the early post-200 years to buy strong positions in the businesses disrupting them? Just how easy was it post that steep stock decline (and associated write-offs of legacy businesses) to make large new investments?

The decline of wholesale electric prices brings to mind another legacy of the change from landline to cellular telephony – the legacy phone world’s assumption long distance revenue minutes would continue to feed their businesses. It never occurred to most telephony executives that the new technology might result in phone minutes becoming virtually free.

But, as or more important than the growth of wind and solar are the new business modalities that those industries are creating. In addition, energy storage technologies and electric vehicles are fast creating new disruptive forces that will yet again force utilities to either embrace not just new technologies, but entirely new business modalities; or face further declines in their businesses.

Being a legacy asset owner of a coal, nuclear and gas generation fleet that decides to pick up wind and solar assets is likely to be every bit as successful as newspapers moving to digital advertising and content – it may give you some new revenues, but it won’t stave off the overall hit to your legacy business that may ultimately kill you.

So what do you do?

First, act while you still have rich cash flows that allow you to invest in the new businesses. Oil industries used to brag that they could buy the entire clean energy industry with a couple months of free cash flow. Ask them how they feel about that today in the face of $50 oil prices.

Second, recognize that your legacy business units are largely incapable of successfully cannibalizing themselves. Most are actively making small investments in new technologies as a way to show senior management that they are “fully up to speed and not threatened by these new technologies.” A sober check of realities is likely to reveal otherwise.

Third, recognize that you will analyze the new businesses in light of how you have run your legacy business and that will be a mistake. Bob Lutz, the former CEO/Chairman of General Motors recently commented that Tesla Motors was likely to fail. In reading his comments it became clear that he was evaluating its chances as if GM were running that business. If it were, he would likely be right. But Tesla is being run by folks who come from much more than the auto industry – they are selling a computer experience on wheels not an internal combustion engine with new features. Even if they were to fail, they have already irreversibly changed the way the car business functions. You need to figure out how to see the new disruptive businesses from the much broader perspective of the technologies they are incorporating – digital, networking, communicative, interactive, etc. They are more than simply new hardware technology replacing the old in a static business model.

Fourth, recognize that what was once a business-to-business power industry that dragged ratepayers along behind it, is now a growing consumer business in which the ratepayer isn’t just a customer, they are both a consumer and a seller of energy and energy services. How many of your senior executives come from customer-facing service-oriented businesses that change at Internet speeds? Think about how well AT&T did with similar changes in their businesses.

Fifth, recognize that many of these changes are not about the technology, they are about the people and the corporate cultures of the companies driving the rate of change. Buying their technologies and leaving the people behind is a sure path to failure. Acquiring the people and trying to get them to integrate into your existing corporate culture is equally likely to struggle or fail. At best, you need to acquire these businesses and leave them largely alone, figuring out possible synergies with your legacy business along the way and recognizing the newcomer is likely to eat the lunch of parts of your existing business units.

NOTES

[1] Source: IAB/PwC Internet Ad Revenue Report Q1 2014

[2] Source: Newspaper Association of America, PEW Research Center: 2013 State of the News Media.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decline_of_newspapers

[4] http://www.niemanlab.org/2012/10/clay-christensen-on-the-news-industry-we-didnt-quite-understand-how-quickly-things-fall-off-the-cliff/ ; http://seekingalpha.com/article/1259661-kindle-is-the-fire-that-burns-brightest-for-amazon-com

[5] http://seekingalpha.com/article/1259661-kindle-is-the-fire-that-burns-brightest-for-amazon-com

[6] http://www.nextbigwhat.com/music-streaming-services-in-india-trends-297/ (chart on left) and http://theunderstatement.com/post/3362645556/the-real-death-of-the-music-industry (chart on right)

[8] http://insights.carnival.io/mobile-is-disrupting-retail-internet-trends/

[9] http://scienceprogress.org/2012/04/an-american-kodak-moment/

[10] http://petapixel.com/2015/04/09/this-is-what-the-history-of-camera-sales-looks-like-with-smartphones-included/ ; http://www.filmbodies.com/newsviews/how-steep-was-the-decline.html ; https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/what-has-story-kodaks-demise-got-do-third-sector-lucy-gower

[11] http://www.marketing-mojo.com/blog/did-facebook-and-google-just-kill-off-the-phone-company/

[13] http://thinkprogress.org/climate/2014/05/13/3436923/germany-energy-records/

[14] http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-08-25/why-do-germany-s-electricity-prices-keep-falling-

© 2015 by resourcient. All rights reserved.